The Price of Peace

31 May 2018 - by

Blog by Professor Stephen Pickard, Executive Director of the ACC&C.

I have always been struck with the fact that Jesus did not say ‘blessed are those who love peace, or think it’s a good idea’. Rather it was ‘blessed are the peacemakers’; those who spend their time and energy toiling for peace. Making peace is one of the great tasks on the agenda in times of violence driven by grievances, ignorance, prejudice and self-interest. The Centre has recently been blessed by a number of visitors from around Australia and overseas who, in different ways have reminded us of the imperative of peace. As I write this I do so under the shadow of many Palestinian protesters killed in Gaza at the frontier with Israel in the past 24 hours. It was also haunting to be reminded by a Sudanese church leader at a recent meeting that ‘he was born in war, he lived through war and he knows nothing but war’. Peacemaking is an urgent and difficult task; certainly not for the fainthearted or those who lack the courage and vision for a better world. One way or another peacemaking requires giving up something of one’s very self. It involves being an agent of healing in a traumatised world.

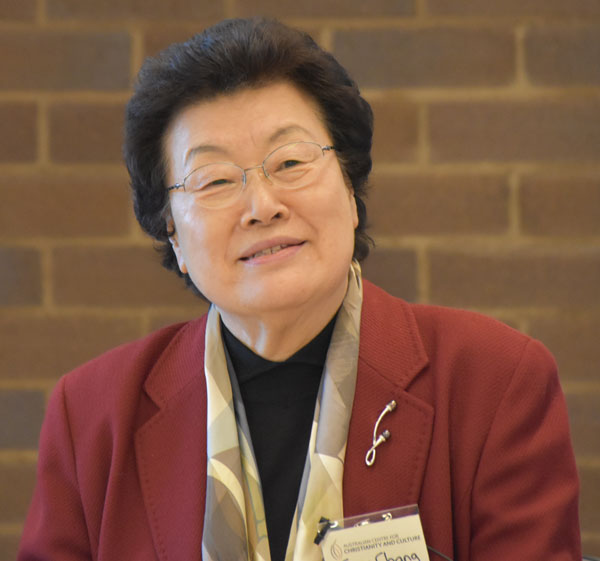

Peace-making between religions was the topic of conversation at the annual scholar’s consultation at the Centre. Our speaker was Professor Ellen Charry (pictured), formerly Margaret W Harmon Professor of Theology at Princeton Theological Seminary and well-known author e.g. By the Renewing of your Minds and God and the Art of Happiness. Her theme, ‘the longest war’ probed the long running division, prejudice and violence between Judaism and Christianity. Charry highlighted the ways in which adversarial binary thinking dominated our cultural and intellectual landscape. This kind of thinking fuelled identity politics as witnessed in the rise of right-wing political parties in the US, Europe and Israel. Charry argued that Judaism, Christianity and Islam have absorbed binary thinking from ancient philosophy, from ancient Israel’s struggle with the nations, and from the circumstances of the birth of these great religions out of one of the others. One result of this dynamic is that each tends to cast the other two as enemies. The consultation challenged us to give more careful consideration to our misperceptions of one another. Overcoming ‘the longest war’ will, it seems, mean that Christians and Jews will have to learn a new humility and respect in the face of the other, and become more self-critical. It reminded me of the advice that the famous theologian Jurgen Moltmann offered to an aspiring theologian: ‘you must learn to divest yourself’. An essential ingredient for peace-making?

Peace-making between religions was the topic of conversation at the annual scholar’s consultation at the Centre. Our speaker was Professor Ellen Charry (pictured), formerly Margaret W Harmon Professor of Theology at Princeton Theological Seminary and well-known author e.g. By the Renewing of your Minds and God and the Art of Happiness. Her theme, ‘the longest war’ probed the long running division, prejudice and violence between Judaism and Christianity. Charry highlighted the ways in which adversarial binary thinking dominated our cultural and intellectual landscape. This kind of thinking fuelled identity politics as witnessed in the rise of right-wing political parties in the US, Europe and Israel. Charry argued that Judaism, Christianity and Islam have absorbed binary thinking from ancient philosophy, from ancient Israel’s struggle with the nations, and from the circumstances of the birth of these great religions out of one of the others. One result of this dynamic is that each tends to cast the other two as enemies. The consultation challenged us to give more careful consideration to our misperceptions of one another. Overcoming ‘the longest war’ will, it seems, mean that Christians and Jews will have to learn a new humility and respect in the face of the other, and become more self-critical. It reminded me of the advice that the famous theologian Jurgen Moltmann offered to an aspiring theologian: ‘you must learn to divest yourself’. An essential ingredient for peace-making?

Peace-making among the churches was the focus of our 4th Ecumenical Roundtable to begin the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity. This

Peace-making among the churches was the focus of our 4th Ecumenical Roundtable to begin the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity. This  year marks the 70th anniversary of the World Council of Churches (1948) and this was celebrated in fine style at an ecumenical service in the Chapel on the evening before the consultation. Our special guest at the roundtable was the Rev’d Professor Sang Chang, President of the World Council of Churches, Asia. Her story of escape (or more accurately divine deliverance) as a young child with her mother from North Korea deeply moved us. Professor Sang and later Dr David Gill unfolded the remarkable history of how the churches of the globe grew closer together in the second half of the twentieth century. The backdrop was a war-ravaged Europe and traumatised world. Peace-making and its companion unity arose out of immense human suffering.

year marks the 70th anniversary of the World Council of Churches (1948) and this was celebrated in fine style at an ecumenical service in the Chapel on the evening before the consultation. Our special guest at the roundtable was the Rev’d Professor Sang Chang, President of the World Council of Churches, Asia. Her story of escape (or more accurately divine deliverance) as a young child with her mother from North Korea deeply moved us. Professor Sang and later Dr David Gill unfolded the remarkable history of how the churches of the globe grew closer together in the second half of the twentieth century. The backdrop was a war-ravaged Europe and traumatised world. Peace-making and its companion unity arose out of immense human suffering.

Peace-making in nations and especially South Sudan was the focus for a national consultation for Sudanese church leaders from throughout Australia from 7 major denominations. This meeting was organised through the National Council of Churches of Australia and co-hosted by the ACC&C. Peace-making is such a fragile and delicate task; it is easily crushed by self-interest; loyalty to tribe and political power. A Unity Statement for Peace was crafted and sent to a high level political meeting in Addis Ababa. We were reminded that the peace we hope for and/or experience in one place is deeply impacted by the existence of peace or war in another place. The Sudanese diaspora in Australia desire to be agents of peace for their young nation of South Sudan. But this required setting an example of what it means to work for peace in their new homeland. Peace-making is tough and complicated. It needs a community of persons committed to helping one another. There are no quick fix solutions. (As an aside, read one of the attendees recent contribution to Crosslight on 'Being South Sudanese, being Australian and being Christian')

Peace-making and Australian’s First Peoples is a matter never far from the concerns of the Australian Centre for Christianity. From 27 May to 3 June each year marks the Week of Prayer for Reconciliation and National Reconciliation Week. We are reminded that in our own backyard there is a deep wound that need compassionate and courageous attention.

There is no such thing as cheap peace. In the Christian tradition, the way of peace is via a hill named Calvary; a tomb for the broken and destroyed; a breakfast by a beach for despairing friends. It is the good God who brokers a new and lasting peace; who breaks down the wall of hostility between enemies and makes divided people into one people. Of course, there is no magic pill for such peace-making. It is a life’s work and at the heart of the life of the Church of Jesus Christ. We are called to be ambassadors of such a peace. This vocation underlies one of the Centre’s 4 Pillars: peace through new religious engagements.

- Australian Centre for Christianity and Culture

- About Us

- Latest News Assets

- The Price of Peace