Love, that most crucial, counter-intuitive act of all - Nick Cave in Faith, Hope and Carnage

06 Apr 2023 - by

Jack Jacobs

Yindyamarra Research Fellow

Everyone has a heart and it’s calling for something

We’re all so sick and tired of seeing things as they are

“Bright Horses”, Nick Cave

“You sitting at the kitchen table listening to the radio.”

Early in Faith, Hope and Carnage (2022), Australian songwriter Nick Cave unpacks the spiritual significance of this otherwise ordinary lyric from his song, ‘Spinning Song’.

The lyric, we are told, captures Cave’s “last unbroken memory” of his wife Susie before the phone rang with news of their son Arthur’s death. Aged 15.

Arthur’s loss – and how this hurled Cave into religious experience – is the subject of Faith, Hope and Carnage. Emerging from a series of conversations had between Cave and journalist Séan O’Hagan, the book explores essential religious themes of grief, defeat, doubt, and love through the ancient art of dialogue. (Dialogue is the “highest spiritual respect that one soul can pay to another in the social sphere” according to Nigerian-British writer, Ben Okri.)

This dialogue arrives at a moment in our culture when people are increasingly sceptical of faith and its association with the institutions that govern religious life. Yet, in the face of suffering and aloneness, many yearn for another way of talking about matters of the heart that are freed from cynicism and control.

Nick Cave – the rocker with a newfound sincerity that breaks with his history of hating the world – might offer us another way of talking about the God.

Jesus Christ has always been at the heart of Cave’s song writing. “As far back as I can remember,” Cave recently told Rowan Williams, “I’ve had a fascination with the figure of Jesus, way before any notion of whether God exists.”

Cave’s Jesus is the wandering Galilean with a “flame-like imagination” who suffers so that he may love. In an introduction to the Gospel of Mark written in 1998, Cave said that: “Christ spoke to me through His isolation, through the burden of His death, through His rage at the mundane, through His sorrow. Christ, it seemed to me, was the victim of humanity’s lack of imagination, was hammered to the cross with the nails of creative vapidity.”

For Cave, as for many mystic poets before him – including St. John of the Cross, Simone Weil and Leonard Cohen – Christ is an artist for whom grief, suffering, and longing are the raw materials into which he fashions an awe-compassionate, all-affirming love for humanity in their broken world.

How did this love sustain Cave through the death of his children? (Another of Cave’s sons, Jethro, died in Melbourne in 2022.) “Nothing happened immediately, except the worst,” Cave told Elizabeth Oldfield on The Sacred Podcast. The death of his children cracked the world open for Cave. Pressure was put on his words to make them break. But then something else happened. “I found for the first time,” Cave said to Rowan Williams, “that I started to become a more complete, fully realised person, as opposed to a personality that was partially formed and fragmented.”

Through grief, Cave found a love and solidarity with all others in the human predicament.

In Faith, Hope and Carnage Cave admits to a frustration with his own inability to give up on rational scepticism and surrender to the idea of God completely. In conversation and in song one hears Cave doubting. He asks questions, not of God, but of himself: “I think of late I’ve grown increasingly impatient with my own scepticism; it feels obtuse and counter-productive, something that’s simply standing in the way of a better-lived life. I feel it would be good for me to get beyond it.”

Between scepticism and surrender, Cave has found a place for the imaginative Christ:

“Rational truth may not be the only game in town. I am more inclined to accept the idea of poetic truth, or the idea that something can be ‘true enough’. To me that’s such a beautiful humane expression.”

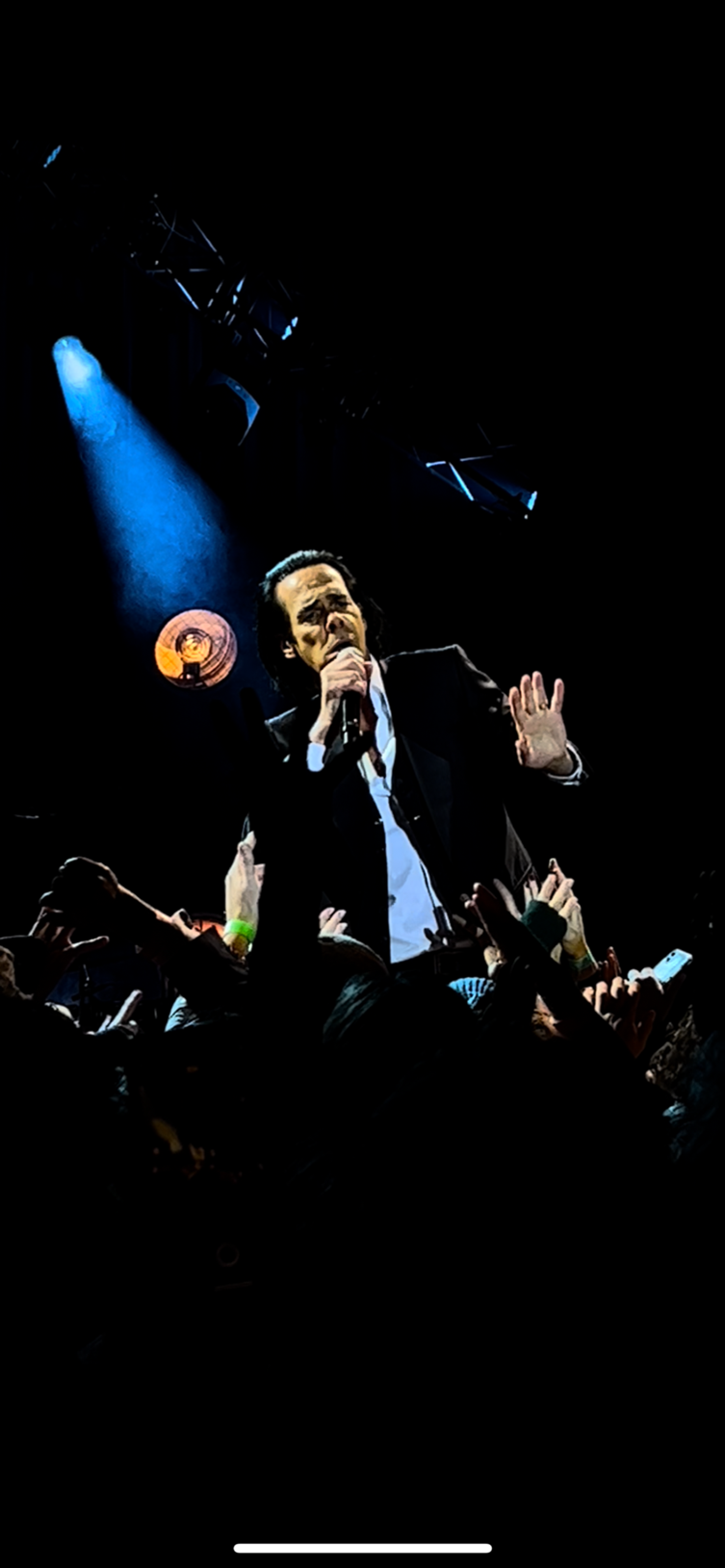

In late 2022, I saw Cave live at Hanging Rock outside Melbourne. As the sun drew down and the fire in the sky chilled to black, Cave came down on the waiting crowd like a deranged, yet peaceful, preacher. Soft in his song. It was clear that Cave had become a conduit for our suffering. Seeing him hold on to the hands of audience members as he sang of grief and hope, I was reminded of Simone Weil’s precious words in Waiting for God: “The love of our neighbour in all its fullness simply means being able to say to him: ‘What are you going through?’”

For Cave, inspired by the imaginative Christ, God is not a proposition to be believed in but a love to be invoked.

The world is a broken place, where we live with broken hearts. But we must resist the allure of cynicism and despair to affirm the world through love. To see the world as worth living in, with loving eyes, is our first task.

Through Cave, listeners and readers might find a way to the Sacred that lies outside institutions on the cracked and beaten path of the wounded heart.

This is another way of speaking about the God in a world that remains forever in need of compassion, imagination, justice, and mercy. One in which, “Love, that most crucial, counter-intuitive act of all, is the responsibility of each of us.”

- Australian Centre for Christianity and Culture

- About Us

- Latest News Assets

- 2023 stories

- Love, that most crucial, counter-intuitive act of all - Nick Cave in Faith, Hope and Carnage