Bonegilla’s beginnings

‘Wir Haben Ein Heim’ aka ‘We found a home’ was made in 1948 and distributed to refugee camps in Europe in the hope that it would attract displaced persons to Australia. The film begins and ends with a young man contemplating his new homeland. Arthur Calwell, the Minister of Immigration, greets the arrival of the first contingent who are destined for Bonegilla. There they discover a warm climate. They are well fed. The film shows new arrivals attending classes to learn English and something of Australian geography. It depicts Australia as a land with large cities, and factories where the newly arrived might live and get work. It explains how Australia depends on primary production, where again there are job opportunities. In the classroom and on shopping excursions newcomers are introduced to imperial measures and Australian coins. They have opportunity to enjoy some swimming in Lake Hume. The film ends with an Estonian men’s choir singing ‘Let’s go men, we have a job to do’.

Look out for

Viewers will notice there is no reference to children. Australia wanted work-ready young men and women.

- The ways Bonegilla was made attractive.

- The ways Australia was made attractive.

- They ways in which the young men and young women seem to be segregated. Why?

- The ways in which the former army huts were turned into classrooms. Notice the classroom display materials, particularly the flags.

- What do you think Arthur Calwell might have said to the new arrivals?

‘New citizens learn our mode of living’, 1948

A second film was made at the same time and distributed within Australia to explain the post-war immigration program to the Australian public.

Compare the two films. How are they alike? How are they different? Why?

Arriving in Australia, 1963

‘Arriving in Australia’ shows what would-be migrants in 1963 might expect on arriving in Australia and at Bonegilla. The film runs for 18.23 minutes. From 8.34 minutes the migrants board a train for Bonegilla and are introduced to the countryside, then the services and facilities at the centre.

- How did the publicists show prospective migrants that Bonegilla was a welcoming place?

- What were some of the difficulties migrants might have continued to face that the film glosses over?

Compare the three films

- In what ways did Bonegilla change?

- In what ways did it remain the same?

- How did those being filmed respond to the cameraman’s presence in all three films?

-

What accommodation arrangements were made Australia-wide for newly arrived government assisted migrants? chevron_right

There were three different kinds of accommodation provided for newly arrived migrants.

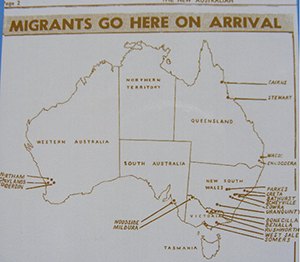

- For the non-British the government established 23 migrant accommodation centres, of which there were 3 Reception Centres and 20 Holding Centres. At near peak occupancy in 1951 they housed temporarily 47 300 people.

- For the British there was another system of 28 worker hostels in centres such as Wollongong, Newcastle, Melbourne and Sydney which offered British migrants immediate employment places. The worker hostels provided an initial settlement rather than an arrival service.

- For unaccompanied children, almost invariably British, there was a third distinct system of accommodation at farm places such as at Fairbridge, pre-war as well as post-war.

The migrant accommodation centres established by the Commonwealth to take in non-British migrants.

The migrant accommodation centres established by the Commonwealth to take in non-British migrants.All the states were to have access to the newly imported labour, so the accommodation centres were established all over Australia. They were usually placed in disused army or air force camps near country towns, but over half of the holding centres were near country towns in inland New South Wales and Victoria. Country towns welcomed the opportunity to supply local goods and services to non-military establishments, as they had to wartime encampments.

There was a reception centre in Bathurst (NSW) dealing with the displaced persons until 1952 and another in Holden (WA). Greta served temporarily as a reception centre intermittently.

-

Which refugee and migrant groups were received at Bonegilla, 1947-1971? chevron_right

There were three main waves:

- First, the Displaced Persons, who arrived from 1947 to about 1952;

- Second, the assisted migrants and Cold War refugees of the 1950s;

- Third, the assisted migrants and Cold War refugees of the 1960s.

-

How were migrants ‘received’ at Bonegilla? chevron_right

Non-British new arrivals were at the reception centre for about three or four weeks while their work arrangements were made. While waiting to be allocated work, they were subject to confirmatory medical checks and received instruction in basic English language skills and the Australian way of life. The centre provided appropriate health-care and helped the new arrivals secure Australian social security benefits.

On arrival newcomers were allocated a hut with an issue of eating utensils, crockery, blankets and linen. If they were in need they also got an issue of clothing. They were given opportunity to check all their heavy unaccompanied luggage had arrived and was stored. Within an hour they were given a meal. Next day, they were welcomed to Australia and Bonegilla. They were tested for language competence and allocated to language classes. Within a few days they registered at the Commonwealth Employment Service and had a job interview. Separately they registered for social services (unemployment and child endowment payments) and an Alien Registration Certificate, which permitted them to live in Australia. They had to attend a medical examination and be X-rayed.

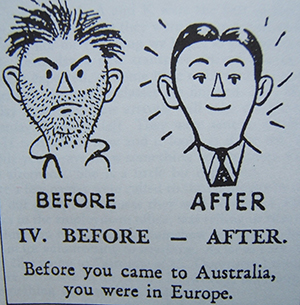

The new arrivals were urged to look forward rather than back. In his customary ‘inspirational’ welcome the Director of the Bonegilla Reception and Training Centre told new arrivals, through an interpreter, that they were Displaced Persons no longer, they were now New Australians. He explained camp discipline and hygiene and outlined the advantages of the country ‘which they have accepted for their future’. He encouraged them to learn English as soon as possible. Bonegilla was about their future not their past.

This processing took only two or three days, but most newcomers were at Bonegilla for three or four weeks while jobs were arranged. When employment was found, the centre staff made the travel arrangements and provided transport costs to the work placement. The District Employment Officer in the state where the migrants were based had responsibilities for any subsequent changes made to their employment.

-

What was involved in communal living? chevron_right

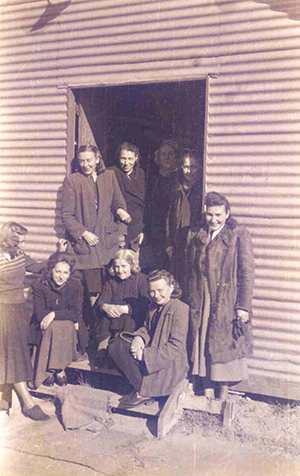

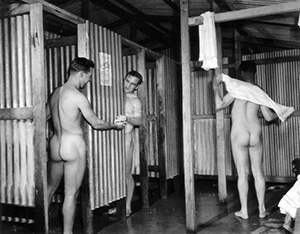

Migrant residents, like the service men and service women before them, ate together in communal dining rooms, called messes. They had communal ablution blocks, usually about 200m away from the sleeping huts. At first they slept in communal dormitories, but the dormitories were subdivided into private family cubicles from about 1952 on. Migrants complained there was little privacy at Bonegilla. The furnishings were simple, including Army camp beds with thin mattresses.

Migrant residents, like the service men and service women before them, ate together in communal dining rooms, called messes. They had communal ablution blocks, usually about 200m away from the sleeping huts. At first they slept in communal dormitories, but the dormitories were subdivided into private family cubicles from about 1952 on. Migrants complained there was little privacy at Bonegilla. The furnishings were simple, including Army camp beds with thin mattresses. -

How were new comers ‘Australianised’? chevron_right

The newcomers were accepted as permanent residents, not simply guest workers. At Bonegilla the aliens would be prepared ‘to take their place in the Australian community’. Hopefully they would eventually develop a feeling of belonging and, one day, apply for Australian citizenship. At the Reception Centre the migrants and refugees would take the first steps in moving from ‘New Australian’ to ‘True Australian’. Beyond Bonegilla there were continuation classes to help them learn more about the English language and what were described as Australian ways.

To give a sense of the new home country and to encourage a feeling of belonging, walls at Bonegilla were to be decorated with pictures of Australian scenes. There was some argument about the best scenes to show, but finally cattle drafting, sheep shearing, a dingo, koala and kangaroo were among those selected.

To give a sense of the new home country and to encourage a feeling of belonging, walls at Bonegilla were to be decorated with pictures of Australian scenes. There was some argument about the best scenes to show, but finally cattle drafting, sheep shearing, a dingo, koala and kangaroo were among those selected.Reception Centre directors fostered engagement with the local community. They encouraged competitive sports, concerts, and handicraft and culinary displays. Interaction with the local community would help the newcomers and members of the host society to get to know each other. It would also give newcomers an opportunity to practise their newly acquired language skills.

Arthur Calwell explained the important role the community had to play in helping migrants assimilate: ‘Our aim is to “Australianise” all our migrants … in as short a time as possible.… It is recognized that, in the final analysis, only the local Australian people … can bring about the ultimate assimilation of any group of migrants in their midst. No language or civics classes, no official wealth program … can supply the need for personal friendship, neighbourly companionship, community of cultural interests and mateyness on the job.’

-

How was English taught to non-English speakers? chevron_right

One of the biggest challenges faced by non-British migrants was the need to learn English. Even the most kindly and well-meaning of staff – the chaplains, the social workers, the language instructors, the employment officers – advised newcomers to learn English and practise it constantly. The surest way into a job was to acquire English. ‘No English, No Job’ was the centre mantra. English was the key to assimilation. Language was the big divide between the new arrivals and the host community.

The language migrants were to learn in their few weeks at Bonegilla was ‘realistic’, rudimentary’, ‘utilitarian’, ‘situational’. The emphasis was on oral English. There was no analysis of grammar. A few model simple sentence structures were offered for imitation. Vocabulary would come afterwards. There were lots of simple repetitive songs to be learned. Residents learnt songs such as ‘She’ll be coming round the mountain when she comes’, ‘Three Blind Mice’, ‘One potato, two potato, three potato more’, ‘Ten green bottles hanging on the wall’.

Some authorities wondered if the instruction was sufficient and appropriate. One critic complained that some in the first contingent left without knowing basic words like ‘food’, ‘money’, ‘pay’, ‘meal’. Attendance at classes was not good. Attendance was made a pre-requisite to employment at the centre. Night classes were arranged for the staff.

Some felt a linguistic dispossession. Without their native tongue they lost the ‘familiarity of daily life, the simplicity of gesture and the spontaneous expression of feelings’. Those with professions lost ‘the assurance of being of service to others’. Some lost their name to something more familiar to Australians. Officials developed a list of names that they thought might be better accepted in Australia. Gordana, a refugee from the former Yugoslavia remembers:

I became Margaret and he {my husband} was Jack. Jack, Jim or John, those were the three names they gave Yugoslav men usually. Women could become Margaret or Maria. If you said, ’My name is Branko,’ nobody would call you that. They just said, ‘You are Jack’. You could be Small Jack, Big Jack or Black Jack, different Jims or Johns, but only one of those.

One of the former residents revisiting Bonegilla as Bonegilla Migrant Experience, ‘Menna S’ from Finland in 1958 was aged 10 on arrival. She remembered, ‘The teacher anglicised my name to, heaven forbid, “Shirley”’.

Many people tried to retain their homeland language and to ensure their children learnt it. Greeks, Italians and people from the former Yugoslavia were the most vigorous and successful in retaining their language in an Australian setting.